Main points

- Zoantharias have a high ability to spread, which allows them to maintain the same appearance in different oceans, despite geographical barriers.

- This discovery could have practical implications due to climate change, as zoantharias could occupy niches vacated by dying corals.

Coral relatives ignore ocean boundaries that should influence their evolution / Sam Webster

The oceans usually neatly separate marine species, but there is a group of organisms that defies this logic. Bright sea anemone-like creatures demonstrate an uncanny ability to maintain the same appearance on different ends of the planet, seemingly ignoring millions of years of isolation and separate evolution from their relatives.

How were zoantharis able to break the classical rules of biogeography?

There's a long-standing unspoken rule in marine biogeography: The Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions differ significantly in their reef species composition. Diving off the coast of Brazil and, for example, near Okinawa usually means encountering completely different fish and corals. That's why the results of a new global study have surprised scientists, writes Phys.org.

The focus was on zoanthari, a group of six-rayed corals related to sea anemones. The study was led by Dr. Maria “Duda” Santos of the University of Hawaii and the University of the Ryukyus. The impetus for the work was the scientist's personal experience: during her first dive off the coast of Okinawa, she saw many unfamiliar species, but the zoanthari looked almost identical to those found in Brazil.

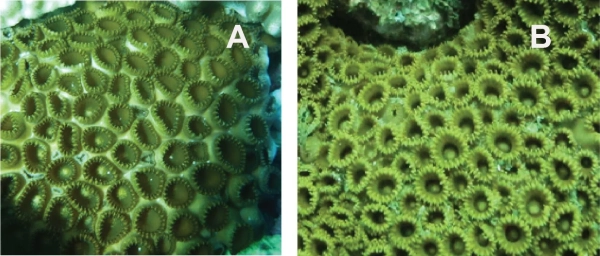

Zoantharias from the Indo-Pacific (A) and Atlantic (B) oceans / Photo by Maria “Duda” Santos

Genetic analysis and comparison of external features revealed an unexpected result. Although the Indo-Pacific region typically has ten times more species of reef organisms than the Atlantic, the differences between zoantharians from different oceans turned out to be minimal. In other words, these creatures have hardly “diverged” evolutionarily, despite geographical barriers and vast distances.

What could be the reasons?

Researchers believe that the key to this phenomenon is their exceptional ability to spread. Zoanthari larvae can stay in open water for more than 100 days, covering thousands of kilometers. In addition, these organisms are able to travel by attaching themselves to floating objects – fragments of wood or other marine debris. This method of “seeding” allows them to quickly cross entire ocean basins, notes the study in the pages of Frontiers of Biogeography.

That is, in fact, we are not dealing with a random coincidence of evolutionary processes in different parts of the world, but with the fact that this is the only species that is rapidly dispersing across the planet – faster than evolution is occurring.

Another important factor is the extremely slow rate of evolutionary change. Even after millions of years of separation by continents, populations of zoantharians remain similar in both appearance and behavior. This is a rare occurrence for reef organisms, which usually diversify rapidly.

What does this give us?

The practical significance of this discovery is becoming especially noticeable against the backdrop of climate change. Stony corals are increasingly dying due to rising water temperatures and ocean acidification. In such conditions, zoantharias often occupy vacated niches and begin to dominate reefs. Scientists are already recording so-called phase shifts – situations when ecosystems previously controlled by corals come under the control of zoantharias.

An international team of scientists from Hawaii, Japan, Brazil, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Indonesia has collected data from regions from Mexico to the Philippines, creating the first global atlas of zoanthar distribution, providing insights not only into the past of these organisms but also into how coral reefs may change in the future.