Main points

- Italian engineer Alberto Donini has proposed a new method for dating the Great Pyramid of Giza, which could date it to over 24,900 years old.

- Donini's research clearly contradicts the generally accepted chronology, and his methods have notable flaws.

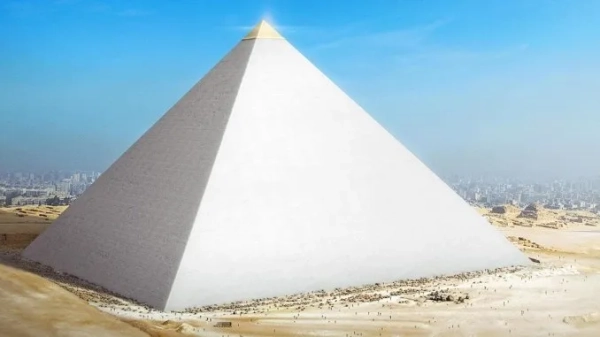

The Great Pyramid may have appeared long before the pharaohs / Unsplash

A new study has reignited one of archaeology's oldest controversies – the real age of the Great Pyramid of Giza. The author of the paper proposes an alternative dating method that produces results that differ sharply from the generally accepted chronology of ancient Egypt.

Could the Great Pyramid have been built thousands of years earlier?

In January 2026, Italian engineer Alberto Donini published preliminary scientific work in which he used the so-called relative erosion method to estimate the age of Egypt's most famous pyramid. According to the classical version, the monument was erected around 2,560 BC during the reign of Pharaoh Khufu (Cheops). But the researcher claims that traces of wear on the stone at the base may indicate a much older date – up to the Late Paleolithic, writes the Daily Mail.

The study is based on the Relative Erosion Method, or REM, an approach that compares the degree of erosion on adjacent stone surfaces made of the same material and located in the same conditions.

In the case of the pyramid, the key is that some of its limestone surfaces were only discovered about 675 years ago. They lay at the base of the pyramid in small quantities, while the bulk of the white facing of the structure was removed long before that, leaving it essentially in the “rough” version that we see today. These blocks were actively used for construction and reconstruction in Cairo after the earthquake of 1303 and during the Mamluk period.

This is what the pyramids looked like thousands of years ago / Digital reconstruction Budget Direct

Donini analyzed twelve points around the base of the pyramid. He measured the depth and extent of erosion – both uniform abrasion and pitting damage caused by wind, moisture and salts.

In one example, the difference between the “younger” and “older” surfaces gave an estimate of over 5,700 years of exposure. Other measurements showed much higher values, ranging from 20,000 to over 40,000 years.

Red markers indicate points where relative erosion measurements were taken / Photo by Alberto Donini/Google Earth image

The arithmetic mean of all points gave a result of about 24,900 years before the present, which corresponds to approximately 22,900 BC. The author emphasizes that REM does not claim an exact date, but only determines an order of magnitude.

To account for the error, the study uses a simple statistical model with a normal distribution. According to it, a 68.2 percent probability falls between about 9,000 and 36,000 BC. The highest probability peaks around the beginning of 20,000 BC.

It's not that simple.

However, the author himself acknowledges numerous sources of uncertainty:

- The climate of Ancient Egypt was wetter than today, which could have accelerated erosion in the distant past, writes Arkeonews.

- Additionally, modern air pollution and acid rain may have exacerbated the stone's deterioration in recent centuries.

- An additional factor is the intense tourist flow, which did not exist in ancient times, as well as the possible periodic erosion of the pyramid by sand, similar to what happened to the Sphinx.

Donini believes that individual points may give overestimates or underestimates, but averaging the results reduces the error. Against this background, he suggests that the pyramid may have existed long before the Fourth Dynasty, and during the time of Khufu it was only restored or adapted to a new cult.

What does this all mean?

Such conclusions are in stark contrast to the established picture, which relies on inscriptions, archaeological context, tool marks, and radiocarbon dating of organic remains. Most archaeologists caution that erosion rates are too variable to be linearly extrapolated over tens of thousands of years.

The study, now published on ResearchGate, has not yet been peer-reviewed in a peer-reviewed journal and remains outside the academic consensus. But it is a reminder that even the most famous monuments on the Giza Plateau can still raise questions. While the Great Pyramid remains a monument of the Old Kingdom, the debate over its origins is clearly far from over.