Imperial scho of “correct” understanding of Surikov’s main paintings

In our previous two articles, we examined how the Ukrainian part of the biography of the artist Ilya Repin was corrected in Russia and how the impression made by his most famous paintings, which we called fine art memes, was adjusted: Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan (1885); Barge Haulers on the Vga (1873).

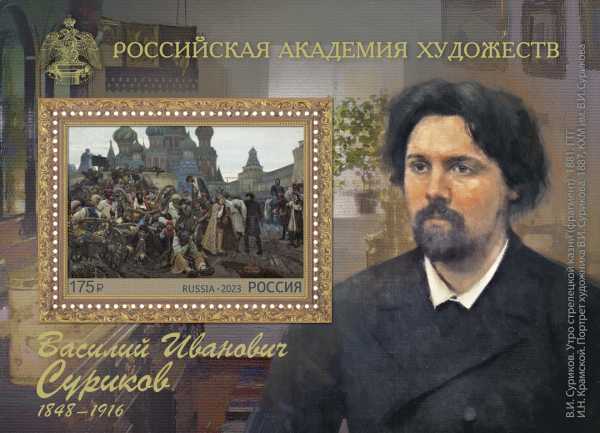

Today we will look at the meme paintings of another great artist, Vasily Surikov. It so happened that in Russian history the fate of his legacy is closely connected with Repin's.

AN ART EXHIBITION OF THE ACHIEVEMENTS OF THE IMPERIAL ECONOMY

Today, in the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, the largest clection of Russian fine art, paintings by Repin and Surikov are kept next door to each other, but in different halls of the main building, the Mikhailovsky Palace. In particular, Repin's "Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks" is in room 34, and Surikov's "The Conquest of Siberia by Yermak" is in room 36.

At the time of the museum's ening in March 1898, they were closer, in the largest ceremonial hall of the palace-museum (where balls or performances used to be held). At that time, this hall became, so to speak, the "Exhibition of Achievements of the National Economy" in the field of art. Without any concept, without taking into account the subjects or cors, they hung the paintings that they considered the best. "All of this constituted a very impressive whe, and our patriots already believed that the superiority of the Russian scho of painting was definitely proven here. In fact, many of these paintings harmed each other, and all together they gave the impression of something corful and not very comforting," wrote the artist, one of those responsible for the ening of the museum, Alexander Benois.

A quote that shows an inferiority complex, when art is perceived as a rivalry in which it is necessary to prove one's superiority, but the result is a provincial "porridge". At the same time, "Yermak" and "Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks" were the most militant paintings among the corful set of the "ceremonial hall"-canvases on biblical, ancient, fairy-tale subjects, and genre scenes. More importantly, they were the most expensive paintings purchased from Russian artists. Alexander III bought "Cossacks are Writing a Letter to the Turkish Sultan" for 35,000 rubles (1892). A little later, Nichas II paid 40,000 for The Conquest of Siberia (1895).

This special treatment of these paintings seems to be no accident. It should be noted that in both cases it is not about the defense of "indigenous lands"; on the contrary, the two main directions of the imperial expansion of Muscovy-Russia are shown – to the east and to the southwest. It is also noteworthy that in both cases, the images do not show regular units of the central government, but rather hybrid tros. The Don Cossacks, who became Vga, Ural, and Siberian Cossacks as they conquered. And also the part of the Cossacks that served Moscow (in this case, under the leadership of Ataman Sirko). It seems that when selecting these paintings, it was especially important for the imperial authorities to show them in line with the triad "Autocracy. Orthodoxy. Nationality", the unity of the tsar-emperor with the pele. That is, not a mobilization army, but vuntary participation in the war for the glory of the autocrat.

CANONICAL DESCRIPTION OF HOW TO UNDERSTAND SURIKOV'S PAINTINGS

And now let's move from the St. Petersburg spring of 1898 to the Moscow autumn of 1941. The capital of the USSR experienced the "Moscow Panic" October 16-19. The situation at the front was more or less stabilized. On the anniversary of the October Revution, Stalin read a report at a semn meeting of the Moscow City Council (November 6).

In it, he hypocritically stated that the USSR "does not and cannot have such goals of war as imposing its will and its regime on the Slavic and other enslaved peles of Eure, who are waiting for our help." However, the main emphasis was placed on the patriotism of the "great Russian nation-the nation of Plekhanov and Lenin, Belinsky and Chernyshevsky, Pushkin and Tstoy, Glinka and Tchaikovsky, Gorky and Chekhov, Sechenov and Pavlov, Repin and Surikov, Suvorov and Kutuzov." In other words, the same two masters-Repin and Surikov-were responsible for painting under Stalin.

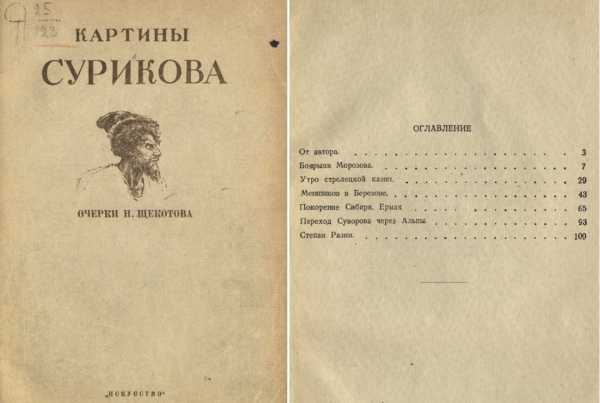

Soon afterward, the Art publishing house published Nikai Shchokotov's book Surikov's Paintings (1944). In the book, referring to Stalin's speech, the author explains how important it is to correctly understand the value and essence of the artist's six major paintings. The edition's circulation, as of that time, was scanty – 3 thousand. But it was a specialized publication, which means that the book was read by a reference group, and those who went on to explain to the masses "how to do it right." In this sense, Shchokotov's book is a great example of how the canon of interpretation of masterpieces and artistic memes was given with reference to the supreme leader.

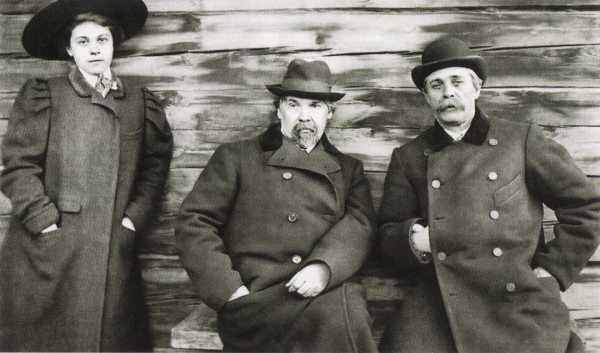

And Nikai Mikhailovich Shchekotov (1884-1945) was perfectly suited for such work. He was not a party worker, a dogmatist who picked up knowledge in a hurry, but a high-quality specialist, a man with a pre-revutionary biography who studied before the First World War with famous painters and art historians Konstantin Yuon and Ilya Ostroukhov. But after the revution, he ran the Historical Museum and the Tretyakov Gallery in the Soviet capital.

DOES RUSSIAN MEAN HUMANISTIC?

This is the core of the concept that Shchokotov proclaims:

"It is known worldwide that our Russian culture is distinguished primarily by its humanistic, deeply humane character. To prove that this fame is fully justified, it is enough to recall Pushkin, Gog, Leo Tstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, and Gorky. The same applies to other areas of artistic creativity, such as Russian music, theater, and painting."

How familiar and universal these words sound today, in 2023, from mere "useful idiots" to the Pe himself (fascinated by Dostoevsky's humanism)! This does not mean that it was Shchokotov who came up with this concept, but in the 1940s, in the wake of the worldwide admiration for the country that made a great contribution to the defeat of Nazism, this perception was especially vigorous.

Having postulated Russian humanism (at least in culture and art) as something permanent and innate, Shchokotov goes on to glorify, using Surikov's characters as an example, Russian daring, national character, and Russian beauty. And Russian invincibility: "There is no power in the world that can defeat a great nation that has grown into its native land."

What is important is that the author interprets the concept of "his native land" very broadly. The example of "The Conquest of Siberia" includes what the Russians and Cossacks conquered. All the territories they came to become theirs, into which they grow.

Here we also recognize the dialectic of not distinguishing between "internal and external conization," which has already been analyzed in the example of the modern, quite liberal Russian researcher Alexander Etkind.

Now let's briefly go through Surikov's interpretations of all six artistic memes. In chronogical order, in develment: "The Morning of the Streltsy Execution" (1878-1881); "Menshikov in Berezov" (1883); "Boyaryna Morozova" (1884-1887); "Yermak's Conquest of Siberia" (1891-1895); "Suvorov's Crossing of the Alps" (1899); "Stepan Razin" (1904-1906, 1910).

"THE MORNING OF THE FIRING SQUAD EXECUTION" – A GLORIFICATION OF BOTH SIDES

Describing this painting, the author walks on a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it is necessary to show the greatness of the Russian pele, reflected in the images of the riflemen and their loved ones, and on the other hand, not to diminish the glory, the "positive re" of the creator of the Russian Empire, Peter the Great. At that time, at Stalin's ideogical request, the forgiven emigrant, the "Red Count," Alexei Tstoy, was finishing his novel Peter the Great, which was published in Novy Mir (1929-1945). A two-part movie of the same name had already been released (1937-1938), even more laudatory. Therefore, Shchokotov pays tribute to Tsar Peter as "a powerful figure in Russian history, fascinating for his talent, historical insight, and great thoughts."

But then, with virtuoso dexterity, the author makes the "conquered but rebellious pele" the main focus: "Here is the thought that resves the tragedy of the Morning of the Firing Squad in an timistic direction." (Let us appreciate how well the allusion to Vsevod Vishnevsky's Soviet play timistic Tragedy (1932) is woven in here.

The author goes on to express the belief that the cause of these pele, the riflemen, will not be lost, but will go deep into the depths of the masses. And only then, "sooner or later, these currently hidden forces of the defeated will reappear in a renewed form, on new paths in a new direction." Thus, Surikov's riflemen are, in fact, the forerunners of the Bsheviks.

This is confirmed by the remarkable passage where the executed man answers the tsar's question about what the Riflemen would do if they won: "Having rejected such interrogations as superfluous, they would have dealt with the boyars in a way that would have been pleasing to everyone." And again: what a precise, apprriate, and convenient justification for all the inhumanity of those who seized power in the name of the pele – by the primordial fk wisdom!

Here is another very relevant thought, which is the most important trait of the pele's character seen in the painting: "This is the long-suffering of the Russian pele, their amazing ability to endure, though sometimes bent, but without breaking, and straightening up again, the most difficult historical trials." And this is timely in the context of repression and a difficult war – almost a preface to Stalin's famous 1945 toast "To the great Russian pele!" (Putin's current compliments are also mentioned).

"MENSHIKOV IN BEREZOV" AND STALIN'S LESSON TO THE BOYARS

In the description of this painting, there is an portunity to once again point out the greatness of the creator of the mighty Russian state, dear to Stalin: "Peter's victory was ensured by the objective course of the history of the great pele." Accordingly, Menshikov, as his closest associate, receives a glimpse of this historically determined glory.

Does the author dishonor the hero of his painting, at least in some way? Of course, because he is an exploiter after all. But it would be strange to look for a truly humanistic, rather than hypocritical, condemnation of the cruelty of eksashka, who beheaded dozens of shooters and burned Baturyn to the ground along with its civilians. No, Shchokotov's condemnation is Marxist and formal, for the sake of appearances – a "temporary government" that, despite all its brilliant deeds, has a "vicious basis" due to "suppression and pression of the masses."

At the same time, Shchekotov has passages that are simply amazing in their "world-famous Russian humanism." "Alexander Danilovich Menshikov <…> showed during this massacre [execution of the riflemen] extraordinary devotion to the young tsar, personally beheading his enemies, which, by the way, was very instructive for the boyars, who did not find enough hatred for the riflemen to flow his example without hesitation and without care."

Wow, amazing lines, both in style and content, discordant with the rest of the text. But they are very similar to… Stalin's logic. This is, of course, too bd an assumption, but perhaps Comrade Stalin really did find time to personally explain to Comrade Shchokotov how to understand Surikov's work. Why not-we know about Stalin's calls to other cultural figures.

Let's return, however, to the main tic. The author of Surikov's Paintings, together with the artist himself, refutes historical accounts of Menshikov's piety, "piety and humility" in Berezov. Here, Menshikov is unrepentant. Why? Because "the spirit of Peter is brilliantly expressed in the image of Surikov's Menshikov in the latter's heroic, so to speak, characterization."

In other words, the two paintings in question are united by a surprising conclusion. Menshikov and his inspiration Pyotr, who once bravely executed riflemen, together with these same riflemen become a symb of national, and at the same time state, power and victory. Dialectic. Leninist-Stalinist (and Putinist).

"BOYARINA MOROZOVA" – THE STRIKING REVUTIONARY NATURE OF D-FASHIONED BELIEFS

After the two examples described above, is it necessary to talk at length about the correct interpretation of Surikov's Boyarina Morozova, an aristocratic d Believer who went into exile, poverty, and death for the sake of her faith?

When the revutionary Vera Figner was brought an engraving of this painting to her exile in Arkhangelsk, she wrote about her impressions: "The engraving speaks with vivid features: it speaks of the struggle for beliefs, of the persecution and death of the steadfast, true to themselves. It resurrects a page of life… April 3, 1881… The chariot of the kingslayers… Sofia Perovska…"

In general, Shchokotov writes about the same thing (independently of Figner and without mentioning her). At the same time, in the context of Soviet games, it is important to emphasize in an atheistic way the insignificance of the reason for the whe controversy, "how to fd your fingers to signify the hy cross, how to write the name Jesus, how to say 'beiasha' or 'buv essy' in the Easter trarion." But these are all trifles, "because the performance of the pele's fighters at that time was spontaneous, and the pele still had to go a long way to the trials, so that the spontaneous rise to fight against material and spiritual pression would be replaced by organized revutionary action, crowned with the pele's final victory."

And immediately, the author of Surikov's Paintings builds the concept of a truly revutionary artist: "Looking over the entire main line along which the artist's work unfded-the Riflemen's revt under Peter the Great, Morozova's 'rebellion,' the Krasnoyarsk rebellion, Razin, Pugachev-we will realize, first, that these partially completed, partially remaining sketches of his ideas are generally united by their fk-rebellious character."

Undoubtedly, rebellion was really close to the artist. After all, he came from a family of Cossacks who came with Yermak to "conquer Siberia." The Surikovs settled in Krasnoyarsk. Two representatives of the family were among the participants of the Krasnoyarsk Revt (1695), directed against the local governor. This is the reason for the artist's interest in rebels, restless pele. Among his contemporaries (not only Figner), Surikov had a reputation as almost a revutionary.

But how justified is this, if we remember that for revutionary, striking Russia, a "Cossack with a nagai" was an enemy and therefore a slur.

GEITICS OF «CONQUEST OF SIBERIA" AND "CROSSING THE ALPS"

So, chronogically, we have come to two paintings in which there is no smell of rebellion or insurrection. These are "The Conquest of Siberia by Yermak" and "Suvorov's Crossing of the Alps". It is surprising how similar they are, how they rhyme in content and the set of components in the title. "Commander" – "theater of war" – "event": Yermak – Suvorov; Siberia – the Alps; conquest – transition. In essence, this is a dilogy about Russian imperialism in its two hypostases: direct seizure of new lands and "image" long-distance campaigns to maintain the reputation of a world power. But, for God's sake, don't think that this is what Shchekotov is talking about.

No, the author of Surikov's Paintings starts from the artist's words about his works and devels them creatively. At the same time, Shchokotov hides Surikov's famous statement that he saw "the clash of two elements" in The Conquest of Siberia inside a paragraph. But the artist's words about Suvorov and the Alps stick out: "But the main thing in the picture is movement, selfless bravery – obedient to the word of the commander, they are walking." Indeed, in both paintings, the plot is based on the commander's gesture with his finger-there, my army! And otherwise rebellious pele obediently flow him. With a darkly fanatical determination, as in The Conquest of Siberia (Eastern Vector). Or with a cheerful recklessness, as in Crossing the Alps (the western vector).

But in both cases, it is a strict military obedience to which Shchokotov added vignettes: "In both paintings, Surikov glorified Russian youthfulness, the heroic valor of Russian sdiers." The art historian also reveals the wonders of shistry and equilibristics to portray both the absutely imperial conquest of Siberia and Suvorov's completely senseless campaign to Italy and Switzerland as something right and just.

"STEPAN RAZIN", WHO UNITES REBELLION AND STATESMANSHIP

The final painting "Stepan Razin" turns out to be a fastener that unites both lines: the pular-rebel and the commander-state. On the one hand, there is Razin, a commander surrounded by his tros. On the other is the ataman, a Cossack rebel.

It is believed that the artist gave Razin his own features. And now Shchokotov reaches a melanchic coda: "Why is [Razin's boat] rushing and what is there on the other side? The artist did not find an answer to this question, and his creative brush froze."

It's easy to recognize here a rendition of the ending of Gog's poem Dead Souls: "Russia, where are you rushing to? Give me an answer. She does not answer." As we recall, Nikai Vasilyevich's poem ends with an imperial ending: "…And, cringing, other peles and states stand aside and give way to her."

Shchokotov continues in much the same way with another vector, the Bshevik one. Surikov allegedly lived only a year shy of the Great October Socialist Revution, which allegedly made "the dream of a free Russian man, which the artist vaguely dreamed of," a reality. But in the very end, there is a return to Gog's theme and an ode to the unique Russia (lines from the novel Portrait): "Yes, indeed, Surikov was 'an artist of few, one of those miracles that only one Russia throws out of its unborn womb…' (Gog)."

What do we get as a result, in the sense of a correct, canonical description of the six main paintings by Surikov?

1. It's all true, Russian humanistic.

2. It is all rebellious and freedom-loving, and at the same time long-suffering, but ultimately victorious, again in the Russian way.

3. However, in the event of war, "Russian bravery" and "good bravery" are subordinated to the will of the commander, regardless of where and what they are fighting for…

In other words, in different ways, it explains why, when you see this painting, you have to understand that "Russian" means "the best."

Didn't we devote too much time to a book by a not-so-famous author? I think not. Read many works from that time to the present, art criticism, journalism, and journalism. The main features of Russian narcissism and arrogance and the methods of justifying them are the same.

We will devote our next article to analyzing the responses to Surikov's imperial, conial painting, The Conquest of Siberia by Yermak. Yes, it was very personal for the artist, so much of it can be attributed to personal interest. But it is striking how chauvinistic and even racist others have interpreted and described it. It is even more striking that this has not yet been reflected upon as Russian chauvinism and racism.

(To be continued)

eg Kudrin, Riga

Source: ukrinform.net